Research

An up-to-date list of publications can be found on NASA/ADS.

I study the origins of weirdly behaving stars with spectroscopy and asteroseismology. My Ph.D. thesis has focused on lithium-rich (Li-rich) red giants and non-oscillating stars in Kepler.

Lithium in Red Giants

Advisors: Prof. Melissa Ness, Prof. Ben Montet, Dr. Andrew Casey

Lithium-rich giants are a well-known population of chemically peculiar stars. Main-sequence stars go through a process known as the first dredge up phase when the star leaves the main-sequence. In this phase, material in the hotter, inner layers is dredged up to the surface, mixing with the cooler convective envelope. During this process, any species in the outer layer that is sensitive to hot temperatures – such as lithium – is destroyed. We expect lithium to be depleted by 1 dex during the first dredge up phase. However, large spectrosocpic surveys such as GALAH and LAMOST have found that 1% of red giants are enhanced in lithium. Many theories have been suggested to explain their formation, such as planet engulfment, mass transfer, and internal production, but no consensus has been established. Lithium-rich giants represent perhaps the most fundamental disagreement between theory and observations in stellar astrophysics.

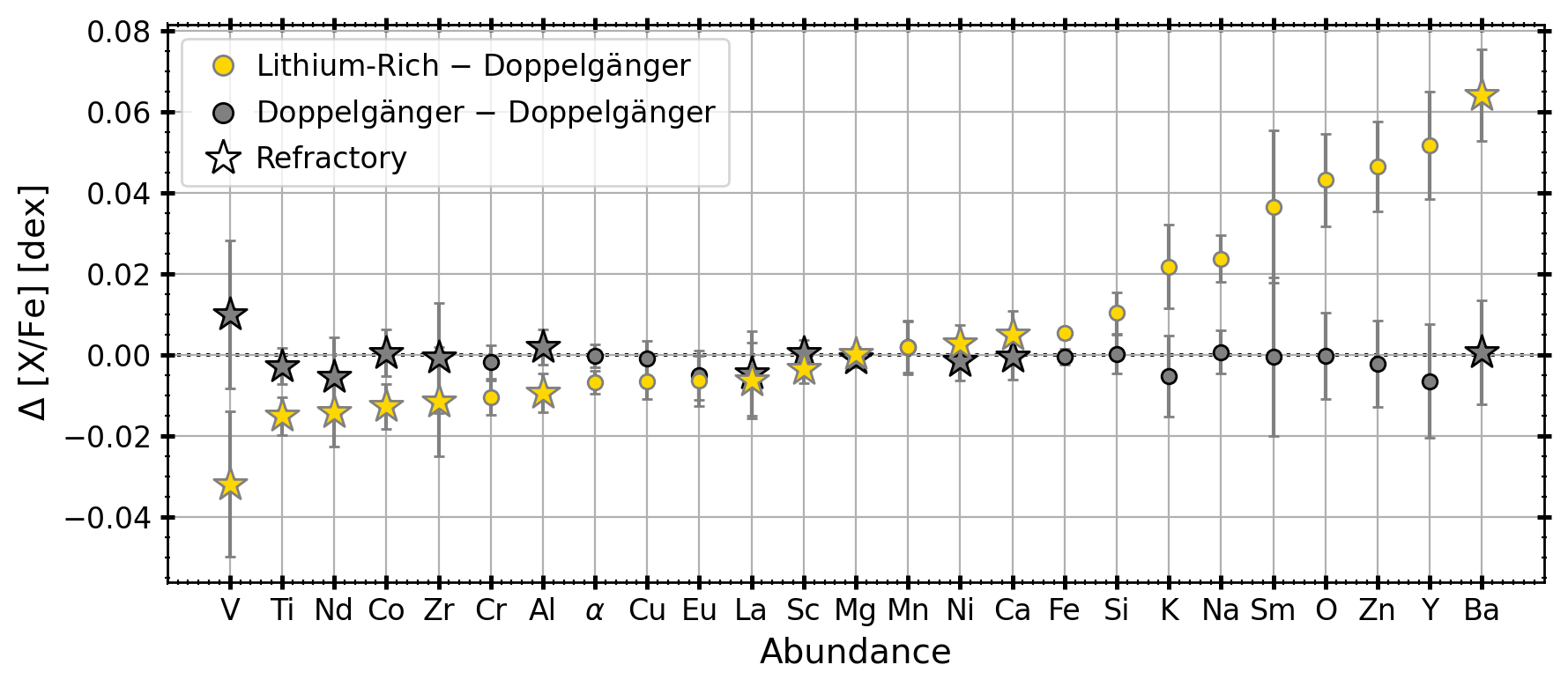

In Sayeed et al. 2024, we analyzed a sample of 1100+ Li-rich red giants in GALAH. By comparing their stellar properties and abundaces against a sample of Li-normal stars, we found mean enhancements in s-process elements such as Ba and Y (see Figure 1), as well as higher than usual broadening velocities for select Li-rich giants. These findings suggested potential mass transfer from a companion, specifically an intermediate-mass asymptotic mass giant branch (AGB) star. However, in order to search for these companions, we first need to understand the binary parameter spaces these objects would occupy. For instance, are they in close or wide binary systems? And what are their mass ratios? To answer these questions, we used population synthesis tools.

Figure 1. By doing a robust statistical analysis, we found that on average, the Li-rich sample is enhanced in s-process elements, such as Ba and Y, as compared to the Li-normal sample. Figure from Sayeed et al. 2024.

In Sayeed et al. 2025b, we used a binary population synthesis code called COSMIC to probe potential binary architectures of these systems assuming the companion is lithium-producing AGB star. Intermediate mass (4-8 $M_\odot$) AGB stars produce lithium via Hot Bottom Burning in their interiors in addition to s-process elements. Our study found that these objects are found at an average separation of 3 AU. Our analysis also suggested that Li-rich giants with A(Li) = 1.5-2.2 dex could have inherited lithium from their main-sequence based on GALAH main-sequence stars.

In Sayeed et al. 2025d, we analyzed radial velocity data of a sub-sample of our Li-rich giants. We collected multi-epoch observations from ESPRESSO, a high-resolution spectrograph on the Very Large Telescope in Chile. Based on observations of 33 red giants, we recovered a companion fraction of 9/33, or 27%. We find that our binary companion sample has a higher prevalence of stars on the red clump ($\log g=2-3$ dex), and with lower lithium abundance (A(Li) = 1.5-2.0 dex). Further data are being collected to distinguish between various formation mechanisms of these objects.

Asteroseismology

Advisors: Prof. Daniel Huber

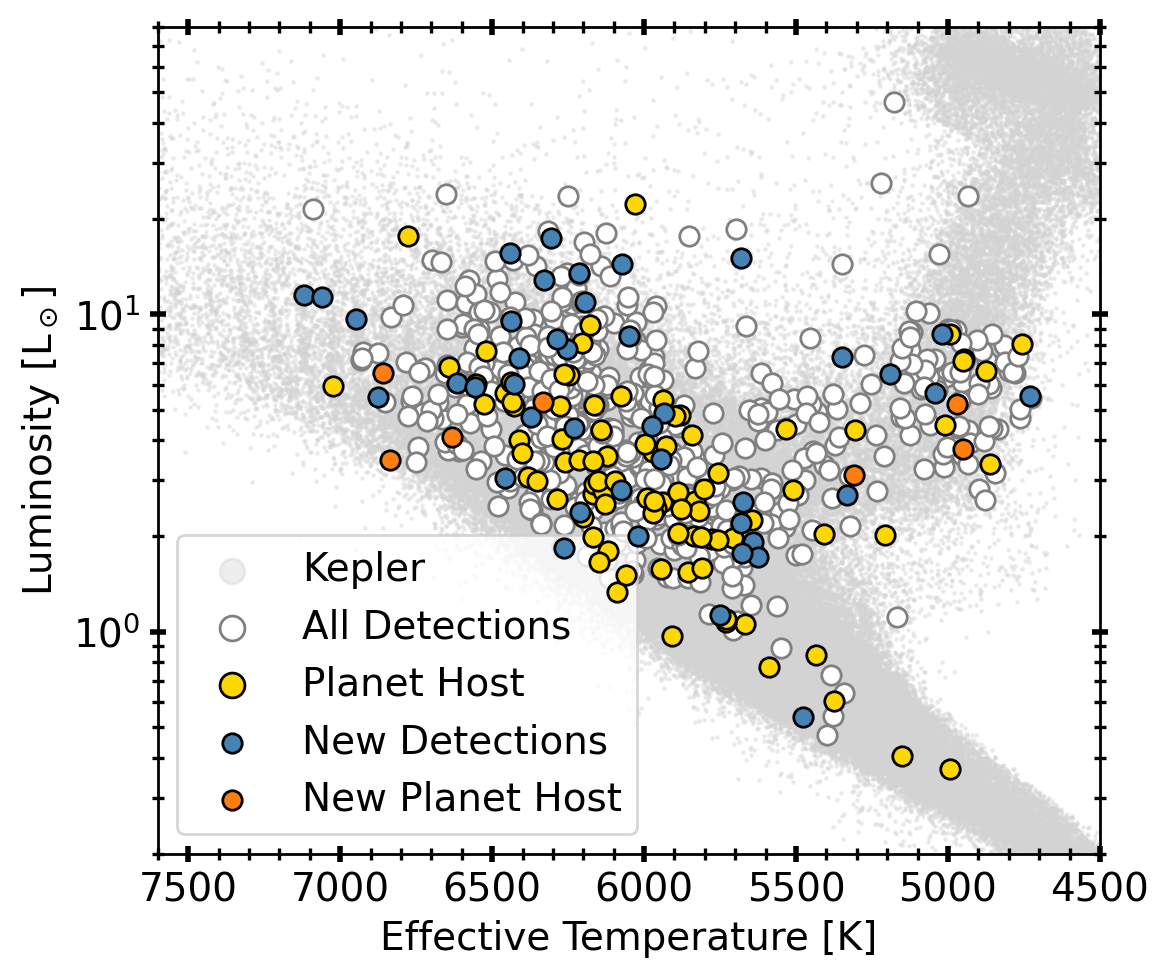

NASA’s Kepler mission revolutionized the field of asteroseismology, the study of stellar oscillations. Asteroseismology is useful for deriving fundamental stellar parameters, such as mass, radius, and even age. These parameters are particularly useful for exoplanet characterization. In Sayeed et al. 2025c, we published a homogenous catalog with 750+ solar-like oscillators in Kepler DR25 data, including 50 new detections, as well as planet hosts and rotators (see Figure 2). This catalog was useful in studying the effects of activity on oscillators and non-oscillators. Specifically, we used surface activity indicators from the Keck/HIRES spectrograph to improve our prediction of oscillation amplitudes. Non-oscillating stars present a challenge to stellar evolution theory; our work suggested that stellar activity modifies convection efficiency in ways that suppress oscillations, providing a framework to predict oscillation amplitudes for targets in upcoming missions such as Roman and PLATO.

In addition, the abundance of time-series observations have motivated astronomers and machine learning experts to find efficient ways of data analysis. While asteroseismology is useful in deriving accurate stellar parameters, it is time consuming to apply on hundreds of thousands of stars at once efficiently. In Sayeed et al. 2021, we developed a data-driven method called The Swan to derive stellar surface gravities using linear regression for 20,000+ stars. The Swan achieves high precision and can be applied for cool stars across the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram (ie. main sequence, red clump, and red giant stars).

Finally, I am a co-developer of an open-source software called pySYD, a tool for global asteroseismic analysis. Based on the IDL version of the code (SYD), pySYD locates the power-excess due to solar-like oscillations, corrects for the background, and provides a measurement of the frequency of maximum power ($\nu_{\rm max}$) and large frequency separation ($\Delta \nu$). More details about its methodology can be found in our JOSS paper.